Tunisia: A revolution in progress

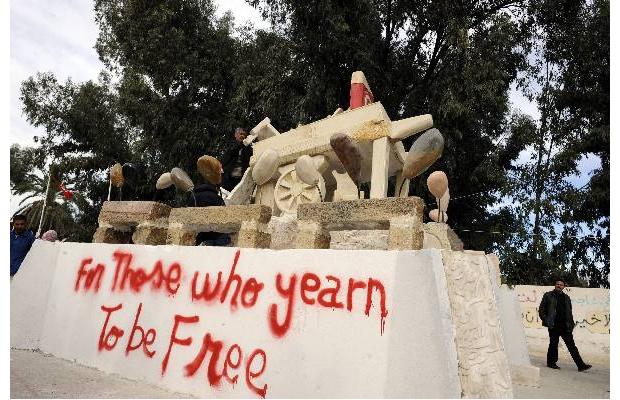

Commemorative sculpture in Sidi Bouzid depicts the cart of fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, whose self-immolation sparked the revolution that ousted a dictator and ignited Arab Spring.

Commemorative sculpture in Sidi Bouzid depicts the cart of fruit vendor Mohamed Bouazizi, whose self-immolation sparked the revolution that ousted a dictator and ignited Arab Spring.

It was my first night in the city of Sidi Bouzid where a humiliated street vendor named Mohamed Bouazizi burned himself to death a year and a half ago – launching the first of several Arab Springs.

From my hotel room it didn’t sound like the revolution was over. Guns were going off under the window of my budget hotel as I watched young men running wild, screaming and fighting with one another.

That May night was typical of my five-month stay from January to June of this year in Tunisia researching a book about the revolution.

Only one night later in the same hotel, I woke up to the cries of a crowd as a young father tried to electrocute himself by grasping a live wire hanging from a nearby window of my hotel. At the last minute he was stopped by the appeal of his children.

Recently, violence and suicide attempts like this have become almost common here. They are a response to the growing desperation of unemployed and marginalized youth who dreamed the Tunisian revolution would change their lives.

“My two sons were in Libya doing construction work before the revolution and they came back hoping to find work. Totally discouraged, they have gone back again,” said a farmer raising animals to feed his remaining three children. “There is no work for the young here.”

Tunisians have elected a provisional parliament that is supposed to be dealing with these problems. But all over Tunisia groups of the unemployed and forgotten have been staging demonstrations.

Chedly Ayari, an economist and former head of the Arab Bank for Economic Development of Africa, says that most of these protests are by young people promised jobs during the campaign for the parliament. “They never got jobs,” he said.

The ruling Ennahda party has virtually ignored the overwhelming social and economic problems that are plaguing this country where 700,000 people are unemployed, 18 per cent of the working population of about 4 million people, according to Tunisia’s National Institute of Statistics. The total population of the country is 10.6 million.

Instead, Ennahda is supporting the spread of practices promoted by the hardline Islamic Salafists, such as more conservative dress for women, censorship of artistic endeavours considered un-Islamic, and suppression of the media.

On July 4, the independent Tunisian authority charged with reforming the media announced it had shut down after failing to achieve its objective, accusing the Islamist-dominated government of censorship, AFP reported. “The body does not see the point in continuing its work and announces that it has terminated its work,” said Kamel Labidi, who heads the National Body for the Reform of Information and Communication.

The morning after

“We are waiting for employment projects to be announced by the central government in Tunis,” one shrugged. “Until then we can do nothing.”

“Nothing” has resulted in suicides as well as angry and depressed gangs of youth roaming the streets and causing trouble.

Watching the angry and frustrated mobs of young, it was hard for me not to think of the “hero” of the revolution, Mohamed Bouazizi who killed himself in December 2010 when he was pushed off the street by a police officer for operating his mobile fruit cart without the proper papers.

Today, an evocative larger-than-life sculpture of Bouazizi’s cart dominates the main street of the city flanked by broken chairs, symbolizing the crash of former dictator Zine El Abidine Ben Ali.

But the powerlessness of the kids on the streets echoes that experienced by Mohamed Bouazizi.

Rejected by municipal and district level officials when he tried to legalize his status as a fruit seller, Bouazizi was then slapped in the face by a police officer. Humiliated and powerless, his response was to burn himself to death with kerosene.

While Bouazizi was still dying en route to a faraway hospital, Khaled Aouainia, an activist lawyer showed up outside the offices of the district government where hundreds were gathering to protest.

“I told the crowd that similar indignities had been happening to all kinds of people in the district of Sidi Bouzid. I told them they shouldn’t be afraid to speak out against the government,” he told me.

On cellphone cameras, tech-savvy Sidi Bouzid residents captured the lawyer’s words and in no time the story was played out on Facebook, then on Al Jazeera and finally on the TV screens of the world.

Abdelwaheb Siliani, a union leader, showed more optimism about the future than some of the civil servants. “When Bouazizi killed himself, people in Sidi Bouzid, were ripe for revolt,” he said.

“Now, there has been success in free elections and the birth of free expression. The current government doesn’t have experience, but we should give them a chance. If they don’t deliver, we can vote for another party or stage another revolution. Now we have freedom.”

The revolution may not have delivered the political changes Tunisians dreamed of but it has liberated ordinary people to find solutions themselves.

In Sidi Bouzid and other disadvantaged areas of the country, activists, most of them women, are on a mission to help newly-democratic Tunisia flourish.

In the café of the hotel where I was staying, I met Sana Hajlaoui, a 32-year-old woman working with an organization in Tunis called Appuie aux Initiatives de Développement.

Sana Hajlaoui, who studied finance and accounting, helped unemployed college graduates organize community projects in Sidi Bouzid.

Sana Hajlaoui, who studied finance and accounting, helped unemployed college graduates organize community projects in Sidi Bouzid.

Operating out of an impoverished neighbourhood, Hajlaoui, who has degrees in finance and accounting, started a centre for young women who had been pulled out of school for marriages that never materialized.

“They were poor and uneducated and kept at home in an area where there was delinquency and abuse of alcohol and drugs. Slowly I gathered them together,” she told me.

Hajlaoui, who is married with a five-year-old daughter, created a program for them that included French classes and sex education along with technical training that gave them a useful skill. As a result, 350 formerly marginalized women are now independent and employed.

In Sidi Bouzid, she also helped a group of young unemployed college graduates organize projects to help the community.

One group is starting an organic farming project working with 100 farmers on huge tracts of uncultivated dryland.

It is being led by Marwen Jellali, a 26-year-old agricultural engineer with a degree in organic agriculture, and Wafa Tlili, a 30-year-old economics and finance graduate.

“First we are looking for money so they can have wells,” said Tlili. “Then we will work with them to develop an organic agriculture project,” she said.

Wafa Tlili (left), who has a degree in economics and finance, and Marwen Jellali, an agricultural engineer, are working with 100 farmers to start an organic farming project on dryland in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia.

Wafa Tlili (left), who has a degree in economics and finance, and Marwen Jellali, an agricultural engineer, are working with 100 farmers to start an organic farming project on dryland in Sidi Bouzid, Tunisia.

Other groups are setting up employment agencies, among them a welcome centre with services for youth looking for work in a small town outside the city.

Enda Inter-Arabe, a microcredit organization with a quarter of a million clients, and a long-time promoter of enterprise in the area, is also working on job creation. In the wake of the revolution, it launched a special loan called Bidaya to support young entrepreneurs.

At the Sidi Bouzid branch, which has over 7,000 clients, Akila Hamdi has been helping 10 young clients with Bidaya loans develop a car wash service, an IT enterprise employing 15, a daycare and tutoring business, and a grocery. So far across the country, 159 entrepreneurs have taken advantage of the program.

Raised in a poor farm family and one of eight children, Hamdi has a degree in management and used to work as an accountant in an auto parts company. “But I am now in my dream job,” she said, “working for the development of Tunisia after the revolution.”

Sana Hajlaoui and Akila Hamdi are just two of hundreds of young development activists I met in Tunisia. Democracy hasn’t yet achieved the political transformation people like them hoped for, but at least it has given them the freedom to try to change their country themselves.

This article was originally published in the Montreal Gazette on Jul 18, 2012.